You are reading a State of Dystopia post. These entries deal with current events that put us on the cyberpunk dystopia timeline. Read them now to see the future we’re going towards. Or read them in the future to figure out where things went wrong.

You can find cyberpunk dystopia just about anywhere in the United States of America, sad as it is to say. But there’s one state in particular that stands out, and it would be best to view it not as some curiosity or one-off situation, but for what it really is:

A warning.

Enter California. It’s the biggest state in the country, home to 39.5 million of the United States’ 328 million people, or about 12% of the population. And it’s got an enormous economy: its 2020 GDP of about $3 trillion would make it the fifth-largest economy in the world if it was a nation.

But fitting California into the label of cyberpunk (specifically, dystopian cyberpunk) might seem jarring to some. After all, California’s sunny beaches stand in stark opposition to the gloomy metropolis or dead cities of Blade Runner.

Or at least, California usually doesn’t look like that.

Outwardly, it might seem like a sunny state with liberal politics and some problems that can be found in many other states. But when you pull back the veil of progressive-sounding rhetoric and great weather, you’ll find a darker picture:

A nation-sized state, dominated by tech companies, plagued by regular environmental disasters, which is probably one of the most unequal places in the world. It might be easy to ignore if you don’t live there, but it’s not just California we’re concerned with here—it’s the future it might herald.

Californian neo-feudalism

Wealth inequality

You likely already know that California struggles with inequality. You’ve probably heard about homelessness in San Francisco and Los Angeles, and you know that rich people live there.

It’s probably worse than you think. Let’s start by considering a basic parameter: poverty.

When you look at the parameters used by the U.S. Census Bureau, the most recently available data (2018) would put California’s poverty rate between 11.8% and 12.8%.

But in the context of the U.S., sadly, 12.8% isn’t even that high. The vast majority of states have poverty rates over 10%. So based on that 2018 Census survey, California is the 26th best of the 50 states when it comes to the poverty rate. Squarely in the middle, if slightly on the worse side.

Unsurprisingly, however, that single Census poverty rate isn’t perfect: that federal definition of poverty was created and standardized in the 1960s and sometimes fails to factor in important aspects of financial stability. So the Census Bureau does have a supplemental calculation of poverty to take into account minor things like…the cost of living.

And if you go by that more nuanced calculation of poverty…

California has the highest poverty rate of any state in the country, at just over 17%.

That’s just what the Census Bureau says. The Public Policy Institute of California says the state’s poverty rate is a similar 17.6%. But according to the Institute, an additional 17.6% of Californians are close to poverty, even if they’re not technically within those bounds.

Meaning, put together, more than a third of Californians are severely struggling. 35% of the state, in poverty or at the brink.

And then, of course, there’s the most visible sign of Californian poverty: a homelessness problem so bad that a UN housing expert on a world tour made sure to visit the Bay Area, alongside the slums of New Delhi and Mexico City.

We all know the tragedy of all this: the poor are next door to people unfathomably richer than them. ‘Cause, damn, California has a lot of very wealthy people. There’s Silicon Valley, of course, and the film industry. But it’s also a national leader in banking and agriculture.

So the state is home to not just plenty of billionaires, but the wealthiest among them. According to Forbes, 100 of the world’s 400 richest billionaires live in California.

For a general sense of how bad Californian inequality is, we can check out the Gini coefficient, which is the most popular way of measuring of inequality. With the Gini coefficient, everything is on a scale of 0 to 1, with 0 being perfect equality and 1 being full inequality (1 person has everything, everyone else has literally nothing). In real life, of course, there are no places with perfect 1s or 0s.

For the data that follows, keep in mind that this is a measure of income inequality. So it’s a low-ball, because it takes into account the millions CEOs get in paychecks, but not the billions they actually hold in assets. Anyway:

If you go by the Gini coefficient, California ranks as the 47th most unequal state out of the 50. But we don’t need to compare only to other parts of the United States. The U.S. is, after all, a pretty unequal country. Let’s put it in terms of nations:

According to the Census, California’s Gini coefficient in 2019 was 0.4866. That would put California between the Republic of the Congo (0.489) and Guatemala (0.483), as the 18th most unequal country among 174 ranked countries. The Republic of the Congo’s inequality surfaces in literal slavery, for context.

Side-note: I am not saying poor Californians have comparable living conditions to poor Congolese or Guatemalan people. I am simply pointing out that the spectrum of inequality in California is equivalent to that of a country with slavery.

There’s another thing that makes California’s case a lot stronger for the category of “neo-feudalism”: property ownership (or the lack of it) and rent-based living.

The comparisons to feudalism here are not just from me, and they go across the political spectrum. Consider these excerpts from a Daily Beast article, written by a conservative pundit, entitled “Landless Americans Are the New Serf Class.”

In Seattle, Miami, and Denver, a household needs to make more than 120 percent of the median income to afford [a] median-priced house. In California, it’s even tougher: 140 percent in Los Angeles, 180 percent in San Diego, and over 190 percent in San Francisco.

[…]The state’s largest metropolitan area, Los Angeles, which includes Orange County, has the lowest homeownership rate of the country’s 75 largest metropolitan areas.

[…]

This drive to intensify development in already densely packed coastal California has strong backing in the academy and the media, and from some powerful real estate and big tech interests, whose primary goal is to house their largely young, single, and often noncitizen workers in dense quarters near their operations.

The trend is everywhere in the U.S., of course, but most visible in California, where high-earning professionals pay substantial portions of their salaries to housing, and the rest are priced out of the area or driven into financial precarity.

Unsurprisingly, the Covid-19 recession has exacerbated this. According to the latest Census data, of 8.5 million rented housing units surveyed in California, over 1 million said they had no confidence in their ability to pay April 2021’s rent.

Psst: You can get more content like this in your inbox. It’s free.

The gig economy

And then there’s the final piece of the dystopian economic puzzle. As more stable work, often carrying higher pay and at least carrying benefits, shrinks, another form of work has sprung up. It’s not extreme to consider gig work second-class employment.

Why a secondary class? The lack of benefits is one big thing. The lack of a guaranteed minimum income is another, as is the fact that gig workers usually have to spend their own money maintaining the things they use to work for the company (i.e., cars). And crucially, gig workers have a fraction of the legal protections given to employees. But even aside from the important material aspects, there’s a new social one: this class of worker increasingly exists to service the consumption of those wealthier than them.

How many Californians are gig workers? Reliable recent data is hard to come by. But we can ballpark: a 2017 UC Berkeley study found that, using a reasonable definition of gig work, 8.5% of Californian workers are gig workers for their main source of income.

Now to be clear, that doesn’t mean 8.5% of Californian workers were in app-based gig work. That sort of work represents a pretty small fraction of gig work, but that doesn’t mean it’s not increasing or setting the bar for the future of independent contractor work overall. (For instance: Uber and Lyft drivers are a tiny fraction of the workforce, but the advent of rideshare has coincided with Amazon making hundreds of thousands of factory and delivery jobs independent contractor status).

We could’ve already generally assumed gig work had increased since that study, but it’s the recent turn of events with the pandemic that probably cemented its role in our economy.

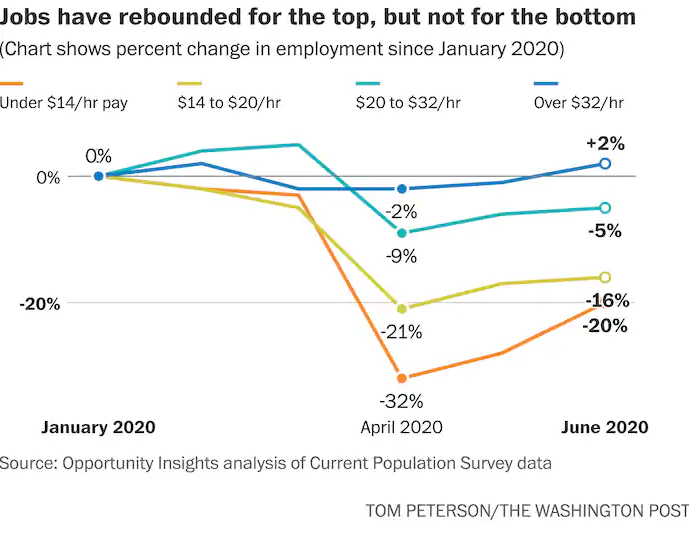

White collar professionals, and most people working in the knowledge economy, were able to work from home with their pay largely intact. In the meantime, the bulk of the jobs lost were suffered by the working class. That’s not just a disparity between the 1% and the 99%, it’s a disparity between the top half and the bottom half.

The worst of the job losses happened for the people who needed decent work the most. But do you remember what happened at the same time those restaurant server jobs were evaporating?

Instacart hired enough people in March-April 2020 alone to more than double its workforce. Similar hiring sprees happened with other app-based gig platforms (though not on such a large scale).

And Amazon? It was seeing so much new business that it had four major hiring sprees from the start of the pandemic to the end of 2020. As of late 2020, Amazon had added 427,000 new employees, increasing its workforce 50% from a year ago. Most of those jobs are in fulfillment—warehouse workers and drivers clarified as independent contractors.

Working in a warehouse or delivery van may not seem as hi-tech as working for Uber, but Amazon insists on making it so. Warehouse workers are subject to constant surveillance, through the use of navigation software, thermal cameras, security cameras, and even wristbands. Amazon has also kept detailed metrics of which Whole Foods locations are most at-risk of unionizing, spied on its (independently contracted) drivers’ private Facebook groups, and more recently, began placing AI-powered cameras with facial recognition in its delivery vans.

Sure, it has yet to be seen how lasting this will be. But as many businesses close their doors for good, and as large companies like Amazon and Walmart increase their presence in every market, it is very possible the economy of the future will feature gig work as a dedicated secondary class of labor.

The disparity may look increasingly dark in the Bay Area and LA, which already feature stark examples of gentrification. It’s one thing for a large population of tech workers to end up pricing out poorer residents from their homes. It’s another when an economic collapse forces those priced-out people to become app-based servants for the white collar professionals who made them go.

One may wonder if this dynamic will hold, given the work-from-home-induced exodus of techies from the Bay Area and other expensive urban areas. We ultimately don’t know whether tech will really leave California any time soon, but I would counter that such an exodus could also simply turn the Bay Area into a place whose key industry has left. Even if housing prices fell, it’s not clear they would fall enough to be affordable to the lower classes, as the US housing market is not exactly tied to reality. Would a San Francisco with the same number of struggling people, plus the economic collapse that follows a key industry leaving, be any less bleak?

A frightening case study: CA’s Prop 22

I’ve talked about Prop 22 several times on this blog, but with good reason. Future fights for redistribution, or against corporate power in general, may look like Prop 22. It’s worth taking notes.

In 2019, California passed a bill requiring most gig employers to reclassify their workers as employees and give them accompanying benefits. Now, you may or may not have fair criticism of that law. But it’s what happened next that should be your top concern:

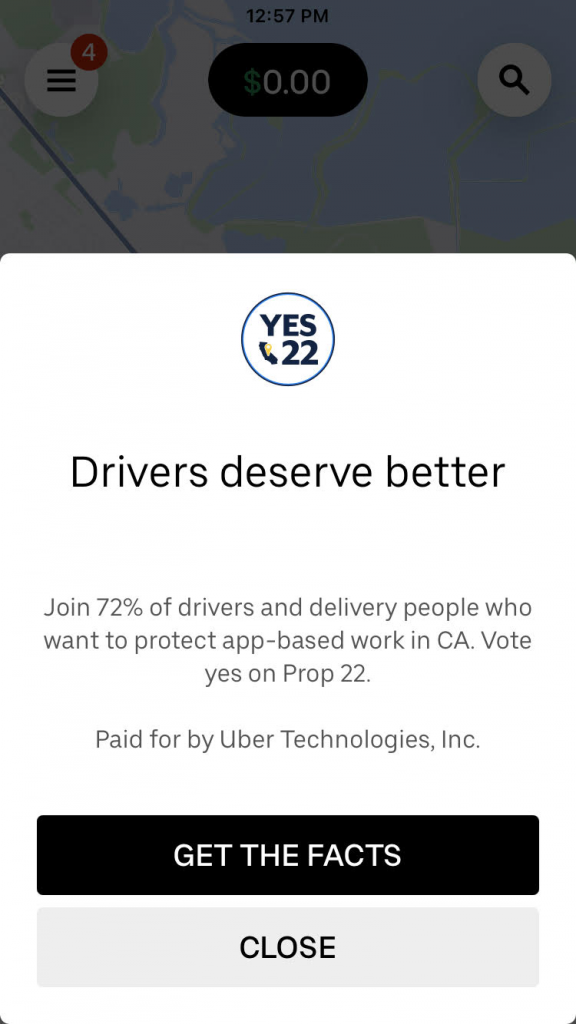

After failing to beat the law in court, app-based delivery and rideshare companies joined together to get their own law passed. Using California’s state referendum system, they got a proposition onto the state ballot for a direct vote, which made an exception from the gig worker law for app-based driving. It was pitched as a proposition to give gig workers benefits, so voting “yes” would seem to be the obvious choice.

What’s key to understand is that Prop 22 did not simply carve out an exception from California’s gig employment law. It grants some increased benefits, but not minimum wage. It bans workers from joining unions. And it takes a monumental 7/8ths majority in the state legislature to even be amended.

Think about that for a second. Big Gig got the state to ban their workers from organizing for better benefits, and to do so with more permanence than ordinary legislation would. Big Gig got a proposition passed that will ensure they never have to give a minimum wage.

The companies spent $200 million campaigning for the proposition. That $200 million blew past the previous record for political spending on a prop, and it outmatched the opposition 10 to 1. But it wasn’t just that they spent a fortune.

They did the most obvious thing, which was also the most dystopian thing, and used their apps to repeatedly message both riders and drivers about the prop.

The messages were so incessant that a group of drivers actually sued Uber for going too far and violating laws against employer coercion. The whole situation is deeply ironic, because if Uber drivers were employees, the messaging would probably have been illegal. But because Uber drivers are gig workers, Uber can tell them how to vote through their source of income as much as it wants.

On top of that, the pro-Prop 22 camp leaned heavily into woke political messaging. It might sound tangential, or overly contrarian, to note this point. It’s not.

How can we hope to avoid a dystopian future if we can’t even see through the superficial discourse used by the powers that be? Corporations employ the language and fixtures of online social justice because it’s an aesthetic that’s easy to adopt, and requires functionally no redistribution of wealth or power. And big corporations will use that language especially when they try to suppress living standards.

A major component of the Yes on 22 campaign’s marketing was the theme that Prop 22 was supported by, and was of most benefit to, people of color. Lest you think this point is a stretch—take one look at the official Yes on 22 campaign site; it touts endorsements by various racial or ethnic advocacy groups, and waxes about how the gig workers are needed to support communities of color.

One of those endorsements most heavily publicized was that of the California’s NAACP chapter. That endorsement was effectively purchased: the campaign paid nearly $100,000 to the consulting firm of the president of the California NAACP. (Though that figure was just small peas compared to the total $1.7 million her consulting firm brought in for backing state propositions in 2020. She resigned over the controversy.)

Many of the advertisements and promotional material for Prop 22 leaned on showing off the companies’ woke credentials. For example, this video by Lyft promoting one of its social justice initiatives, which was overlaid with the recitation of a Maya Angelou poem:

Uber plastered the state with billboards like this:

That’s a curious choice of language on the billboard, by the way. It’s *remarkably* similar to the language used in support of Prop 22. Drivers have the right to work their own schedules. Riders have the right to move around affordably without their own cars. Black people have the right to move….with Uber! The subtext of such billboards, the co-opting of a popular effort at social justice, ought to be considered wildly offensive.

Being skeptical of this social justice marketing doesn’t mean being opposed to social justice, and that is all the more the case because Big Gig primarily employs people of color. Big Gig cited that fact to argue regulating gig work would disproportionately harm people of color. That makes them sound like their side is the one of social justice, until you remember they’re arguing that they don’t need to pay that majority-minority workforce a minimum wage in the most expensive housing markets in the world.

And perhaps most disturbingly, Big Gig’s marketing was effectively signaling to the wealthier voters of California that they could vote to suppress the wages of their app-based servants without guilt. Moral permission: We know you’re socially liberal, but you also want to continue your lavish consumption. Don’t worry, we can solve any contradictions there.

The short version of Prop 22, the reason you should care? It happened in one of the most unequal places in the world, during the worst economic crisis in nearly a century. It can probably happen where you live too, and the next time may not be limited to only app-based drivers.

You might think I’m overreacting, but at least I’m not alone: Human Rights Watch called it “a devastating blow to the rights of app-based workers.”

Environmental crises

I suspect this needs little explanation. When even the Reddit normies know to slap Blade Runner 2049 music onto drone footage of orange-sky-San Francisco, something’s not right.

We all know about the fires, and by extension, the drought that preceded it. But it’s good to remember they intersect with an overarching problem: heat. Even a future California without the enormous fires would have plenty to deal with on the basis of heat alone.

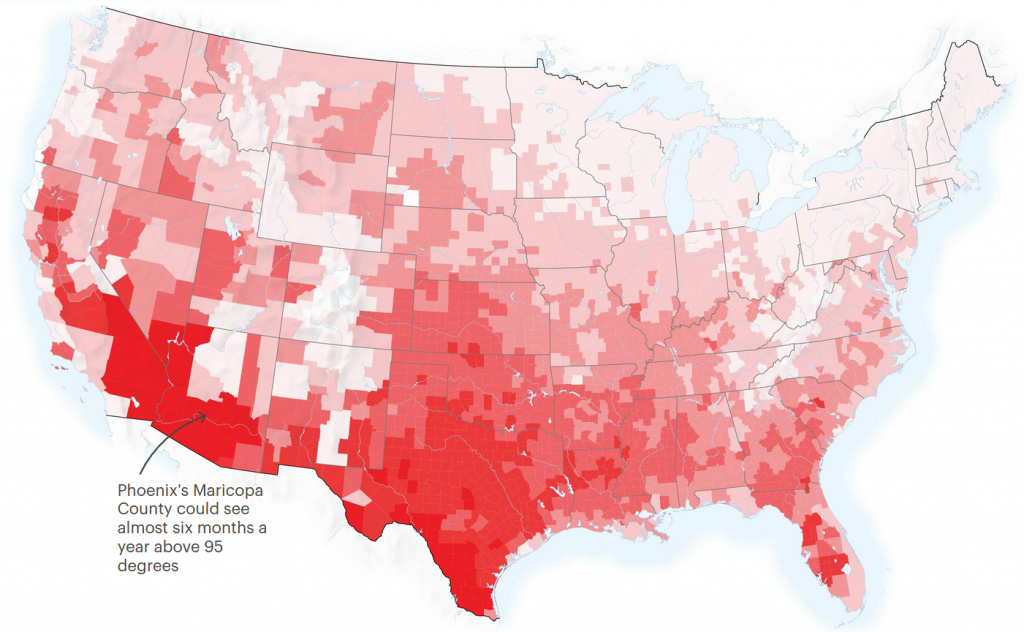

Researchers are now seriously investigating the possibility that climate change could make some parts of the planet too hot for the human body towards the latter half of the 21st century. A detailed study by the Rhodium Group, New York Times, and ProPublica on various climate challenges facing the U.S. put such dangerous temperatures as a potential problem for California.

This map might help us visualize it. The shade of red indicates the number of weeks a year that a county would experience 95-degree heat by the mid-21st century. Dark red means 26 weeks, or about half the year.

Now to be clear, that’s the worst-case emissions scenario (RCP 8.5). It’s not inevitable, and climate modeling is not a perfect science. But even a moderate-case scenario results in substantial parts of southern California being intolerably hot and losing valuable cropland. Or think of it this way: if the worst-case scenario has half the state becoming uninhabitable, how good is the realistic best-case scenario?

And if the trend of climate news meeting or outdoing the worst predictions continues, such heat could even arrive earlier. One recent study suggested parts of California could see intolerably extreme heat waves earlier than the expected mid-21st century.

It also seems quite likely that California will suffer from rising sea levels. It probably won’t be as unlucky as Florida (substantial parts of which may disappear), but it’s still vulnerable. A 2017 report by the state’s Oceanic Protection Council said that major coastal areas could likely see several feet of sea level rise by the end of the century. That report was intentionally conservative in its estimates, with the researchers noting that a 10 foot rise would be unsurprising. The state’s Legislative Analyst Office recently said a 4 foot rise would mean daily flooding in the Bay Area’s poorest neighborhoods, if you want an example of what these numbers translate to.

In 2019, the Office used similar projections to suggest the state would need to start building inwards—just a measly 100,000 housing units every year in coastal areas, starting now. That’s on top of the existing 100,000 housing units built across the whole state every year.

And as for air pollution? Well, California’s cities aren’t even close to New Delhi status (though that shouldn’t really be your goalpost). But, California’s cities are some of the most air-polluted in the U.S., and raging wildfires don’t help. One recent study of the last 3 years of U.S. air quality found that, of America’s 10 worst cities for air pollution, 6 are in California. That’s despite many parts of the state improving significantly. Los Angeles is much more breathable than just 15 years ago, to say nothing of the 1980s. How much of that progress will be set back by wildfire smoke, we have yet to see.

Anyway, all of this amounts to three of the four classical elements: water, air, fire. All California is missing is earth…

I’m not making predictions. Not my field of expertise, and science doesn’t really know when “the big one” would hit anyway. All we can do on this one is prepare and hope for the best. True, earthquakes alone aren’t particularly cyberpunk, but a big one would certainly would make an already-cyberpunk place even more dystopian.

Warning, not future

The operating word in the title of this post is first. There is no reason to think California will be the last or only cyberpunk state. Every state struggles with inequality, costs of living, corporate power, environmental catastrophe, and so on. California just stands out the most right now, with the most visible confluence of all those things.

California’s uniqueness is not something novel to ponder idly; it’s a warning. “Warning” does not mean “the future,” or “inevitable.” So let’s take the lesson the state offers us.

Individual consumption choices can’t swing things, nor can demanding corporate diversity or insisting upon the adoption of modern social justice language. Talking ‘correctly’ about racial justice is doing fuck-all to give black Uber drivers a living wage. Gavin Newsom’s inspiring words on prioritizing climate action have hardly slowed his approval of new drilling permits: the 1,700 permits granted in 2020 were an increase from 2019.

The biggest lesson out of California is this: if it does not seriously challenge power, it will not avert dystopia. California is as “progressive” as states come, but because today’s progressivism is not preoccupied with challenging concentrated power, California’s liberal disposition has had relatively little impact on its standards of living.

Don’t be too hoodwinked by the blue-red dividing line you’re used to. A very simple, relevant, and recent example: in the 2020 election, the blue state of California voted to entrench app-based gig work without any pay guarantees, while the red state of Florida voted to increase its minimum wage to $15 an hour. Actually, $15 an hour won in Florida by much larger margin than Trump won over Biden. Is this fight so impossible?

If there was ever a time to organize, it’s these next few years, when the unfairness is so brutally clear, and when there are still openings to stop dystopia from crystallizing. For all the opulence associated with this country, a large swathe of Americans are poorer than they seem. And in 2020, the world’s richest people, who are also California’s richest people, got even more fantastically wealthy at the same time that about a third of the state got thrown under the bus. When millions of Californians couldn’t go outside because the air was too dangerous, the business of outfitting mansions with luxury air filters boomed.

It’s the combination of these last decade’s scariest trends, on such prominent display, that make California this country’s first cyberpunk state. By that same token though, you couldn’t ask for a clearer message. California reeks of a bad future—but at least it’s a great warning.